Hi Yana! How is everything going – did Sandy disrupt any of your plans?

Luckily we have been safe and sound in my part of Brooklyn, only lots of scary winds…

the “post” Sandy period I think has been much more difficult to cope with in the entire

city, and it will take a long time for a full recovery.

Yana Dimitrova and Sebastien Sanz de Santamaria: Common Frequency

atRadiator Gallery

Common Frequency – an exhibition at Radiator Gallery, NYC, featured

some of your works last month. What was your overall impression of the

exhibition and can you tell us a bit more about the works you presented

there?

The basis of the curatorial idea was in my opinion an interesting one. The show was

curated of creative couples, and it was not necessary that both partners were visual

artists. It really engaged everyone outside of the individual, and into creating work in

relation to one another. Ultimately it promoted a rather collective thinking, which to

me is exciting and very important.

This conceptual set up made my partner and I realize how much we influence each

other, even if not both of us are practicing artist. My work is often inspired through

conversation and dialogue or I often discuss my ideas with my partner sometimes just

to understand what I am trying to do, and his response often can push things in

another direction.

I find that such mindset really creates a fluid, ever evolving matter, and in such most

exciting things happen. The works that I exhibited were in fact a very direct depiction

of our domestic life in the United States. The “Eat Faster” is a table cloth with a

classical pattern with an embroidered text stating “eat faster” interlocked in the design

of the fabric.

I wanted to suggest the inability of such type of domestic life to sustain, while we eat

we send e-mails, we work we talk about work, particularly in such place as New York

you tend to just basically eat faster then ever. With this piece I was interested in

contradicting the historical relevance of the pattern, the function of a table cloth and its

very inability to sustain itself in that context.

You were born in Bulgaria. In what ways do you think your background

influences your art?

Recently I have been thinking about what type of work I would have made if I never

left Bulgaria, and I am certain it will be very different than what I am making at the

moment. I guess as an art student in the U.S., I went through a number of waves, and

tendencies, concepts.

Starting from ideas of Melancholy and Nostalgia to political and ideological conceptual

work, and I find my background prominent in almost everything I have created. I

moved to the United States with my entire family and this really fractured my

understanding and idea of “home”. Whichever country I visit, I feel that there is

something missing, on one side the parents, on the other the culture.

In such position I found myself thinking of concepts of liminality and in-between. The

space between possibly reality and fiction, home and not, things that are not black or

white, a state very exciting and rich in many ways as it has endless possibilities. These

concepts have been key to my practice and conceptual motivation for most of the time

I have been abroad, so Yes my background is definitely in the very root of my work.

Additionally I am always comparing every day for nearly 11 years now how different

things are, with just the entire surrounding and understanding of the world,

mentality…etc.

How did you decide to become an artist?

I don’t think I ever made a conscious decision, but it feels that I have rather been

following a way that I always knew is the right choice for me. I vaguely remember one

day in the kindergarten when we had free drawing time, and the teacher, rather

“Comrade” at the time, kept expressing how my drawing was the best of all.

My friend who was sitting next to me said: “If you draw this pin exactly as it looks, the

teacher is right, otherwise I don’t believe you!” So I had to prove that I really can draw,

and I put forth all of my concentration and drew the pin ( it was of a penguin) and it

looked exactly the same to me at that time. The girl was so impressed- “OK I believe

you! It looks exactly the same!” Meanwhile the whole row of students turned at me

and started asking me to draw those things; it turned into a crazy moment of

recognition at the age of 6. Then I guess I kept going on and on…

You were educated both in Bulgaria and the United States. Where there

any significant differences in the teaching methods you were exposed to in

the two countries?

Indeed, I did feel that the difference was prominent. The very main difference, I think,

was the approach. In Bulgarian academia, the general idea was that you need to

master all representational techniques in order to be creative. Here we had a few very

basic drawing and design introductions but generally after that the big question was:

what is the idea that supports the very specificity of the use of paint?

Why even paint or draw or any of it? I don’t know if one is better than the other, I

think sometimes you need more strict structure in order to create something exciting

in response to that. I find it also problematic that a lot of art schools in the United

States are very expensive, and that promotes a different kind of thinking.

In my experience after I moved to the U.S. I felt that colleagues and professors were

too excited about how accurately I could paint in a representational style, and for a lot

of the students this was a goal. For me the goal was to step away from that and it

created a sense of confusion in the beginning until I set my own goals.

Jan-Michel Basquiat famously said: “I don’t think about art when I’m

working. I try to think about life.” What would your response to that be?

I think that the boundary is totally blurred. The world, politics, economics,

demographics, ideology, your daily coffee, your train ride… it is a way you see the

world not separate from the world. Everything is interrelated in the means of

creativity, in my opinion and that connects to exploring different ideas, different

identities, challenge the world, yourself, others, systems, color, everything. Those

connections need to exist in order to shape critical thinking in not only the artist’s

mind but everyone else.

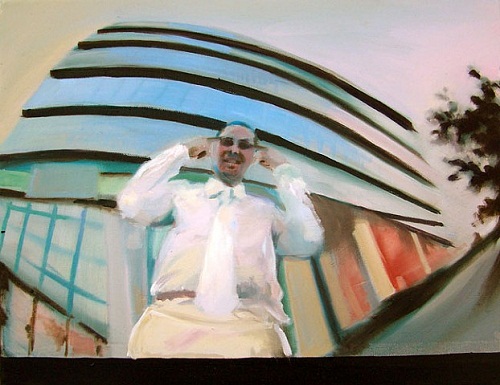

Your works have been exhibited both in America and Europe. Does the

way the audience perceive your art differ from country to country or even

from city to city?

Yes, and there are so many factors for that. Of course people respond to different

things differently, depends on the work and also the context. But generally there is a

difference in taste and aesthetic that people identify with depending on their

surroundings, environment, access to information.

This very difference makes things even more exciting to me. The last exhibition I had

in Atlanta, GA I deliberately created work that might be a bit more critical specifically

to the demographics there, and this set a tone for an interesting reaction.

Can you tell us about your work space and your creative process? What

spaces, surroundings or times of the day prove to be most productive for

you?

I am always ready to create; generally I am so busy all the time that when I am at my

studio I make sure I am on point. I teach art and mural painting during the day and try

to spend the early mornings and nights in the studio. I am lucky to say that my space is

very unique. I work in an old military base which was built in 1917, it was

predominantly used for redistribution and storing of supplies.

The experience of walking through a tunnel next to a train and surrounded of freight

balconies is very interesting and inspiring sometimes. It is also very close to the

Hudson and you can see the statue of liberty, Manhattan, New Jersey, Staten island

and a lot of cruise ships and police ferries. You can walk on the pier where there are so

many fishermen, mostly immigrants. I really find it inspiring. You really can see and

sense the history there, which as a European, it is not something you can experience

anywhere in the U.S. Funny enough, most of my visitors always associate the building

with my background coming from eastern Europe.

No too long ago “The Window at 125” showed your installation “You Made

It.” – a work you designed specifically for that site and with which you ask

a very important question: “You made it. And now what?”. What would

your own answer to this be? And could you tell us how you specifically

“made it” – to the United States, to NYC, to the galleries there – what were

some of the greatest challenges you encountered on your way and what

does success mean to you? In other words, when would you feel

comfortable to tell yourself that you made it?

I think we live in a society that does not want you to believe that you did in fact make

it, simply because if you did, you will have to feel satisfied. Obviously the current

consumerist logic does not allow you to be even remotely in that mindset.

Additionally, if you “made it” it means you need to stop, or start over and both of

those are extremely difficult ideas to grasp. In my experience I am not concerned with

“making it” but probably just the idea of not stopping.

I am always running and part of me thinks that because I left my country it is much

too hard to stop. Productivity, being efficient, being “happy” all of these concepts for

what might construct a successful person, or a great man who will be making great

history, are some I often criticize and question in my work. All of these concepts to me

are in the way some times of human advancing, if you start analyzing the “here and

now” and do this in a much more detached of yourself way that might be just as valid

as success.

It is also another very self-motivated idea, in which one competitively excludes

themself from the whole, and in such remains a split. I walk to my studio I say hello to

the coffee lady, I get in my space I have time to think and create, I engage in a good

conversation, I often teach, I have a platform to exhibit and share some of my ideas,

that is to me success; In ways, appreciating the current while positively engaging

in the future.

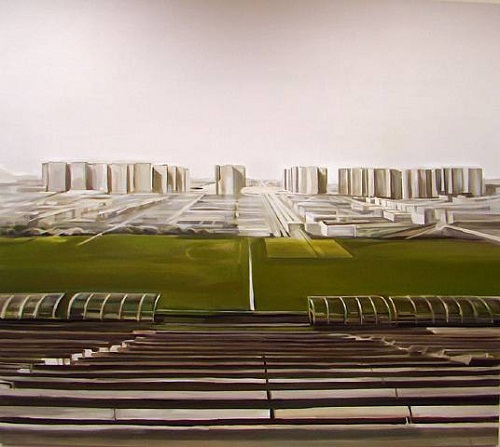

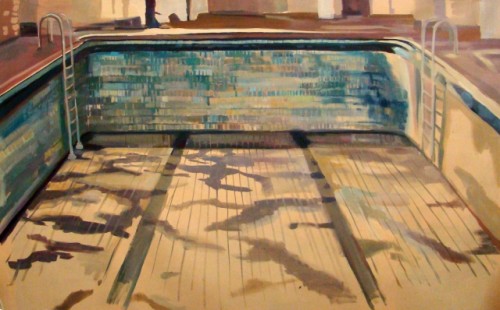

Space seems to play a crucial role in your work – both in your paintings

and installations: landscapes, an empty swimming pool, interior and

exterior of buildings, etc. – do you think they have their own meaning and

existence even when they are completely desolate and abandoned by

humans?

Yes, space is the very invisible matter in which ideology, politics and history lingers. It

is a very psychologically rich matter; the way space is arranged can manipulate the

human experience weather you are in the space or observing it. Previously I have been

so fascinated with the idea of “space in between” or liminality, space in which anything

can happen or not. Your space immediately reflects on your mindset, it is inevitable.

I often portray the space as a dislocated one, or as a deceptive space, where you feel

like you could walk in due to the scale but after “entering” such space you realize it is

criticizing you, and this can be very discomforting. I think this is an important aspect

of my work, the sense of discomfort in order to experience this very sense of transition.

What message does your art communicate and what do you think the role

of the artist in our world should be and especially of the “dislocated”,

traveling artist?

This is a very relevant question, I think it is important that when you do travel from

one place to another you are aware of how much each side can benefit and work in an

engaging way, and not as if you never left your previous location. We have been raised

in a system different than the one in the United States and I find that very interesting

as a point of reference when we talk about the current times, the world or the future.

The angle in which we see the world is different due to that experience imbedded in us

(or at least my generation), maybe we are able to see and experience the world from

many exciting points and facets. With my work I often try to questions those very ideas

of dislocation, disappointment and effort to success outside of your home place, and

therefore completely decompose the meaning of the word success.

My aim is to have a critical discussion, not necessarily propose a solution. I think the

artist’s role is to critically engage in the world, and through a unique way of

communication suggest a different perspective of everything, sometimes maybe

shocking, in order to stir people’s idea an perception of the world.

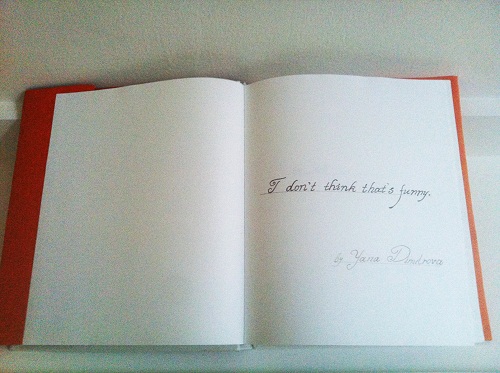

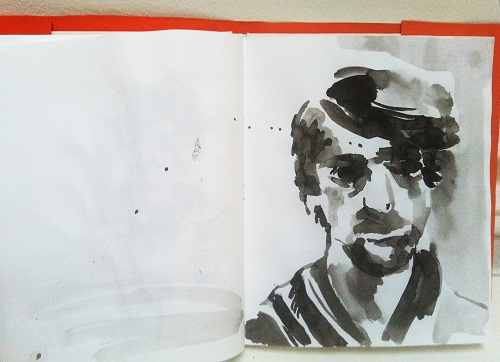

You created a unique book called “I Don’t Think That’s Funny”. In it, you

translate Bulgarian anecdotes into English and accompany them with

illustrations. Why don’t you think they’re not funny?:) And what’s the

backstory on this project – how did you come up with the idea?

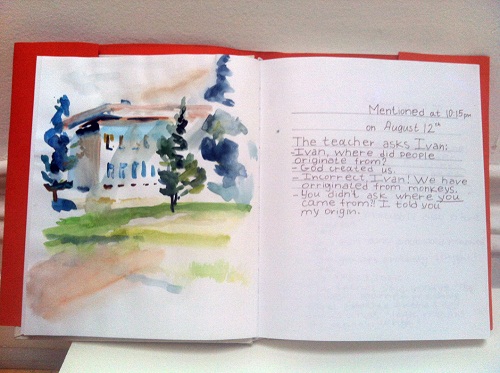

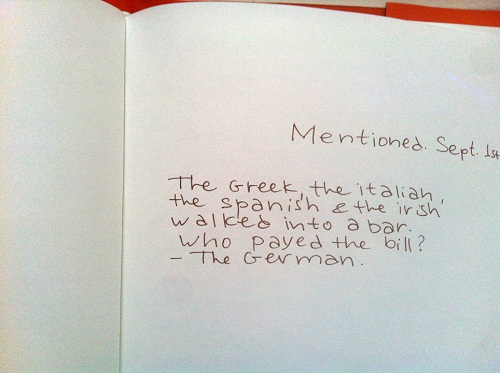

There are so many words and anecdotes that are culturally untranslatable.

I experience that with Seb, my partner, all the time. He is laughing at how not funny a

lot of the jokes I tell him are. Another example of lost in translation as a reaction to the

globalized world, it can’t really translate all the way. It is ridiculous how many times I

have been in meetings or just with friends in which I would try to say something funny

and it ends up being totally a disaster, and I thought why not put all of these in a book.

I also think there is a very big difference of mentality and what we actually find funny.

Bulgarian sense of humor is very dark at times and cynical, and here the general crowd

wouldn’t really think that things that are really taboo are that funny. During the

opening Seb and I created a collaborative performance, in which we set up a

microphone a simple spot light and invited the audience to come and recite a joke that

is not funny. It was actually pretty funny.

What are you currently working on?

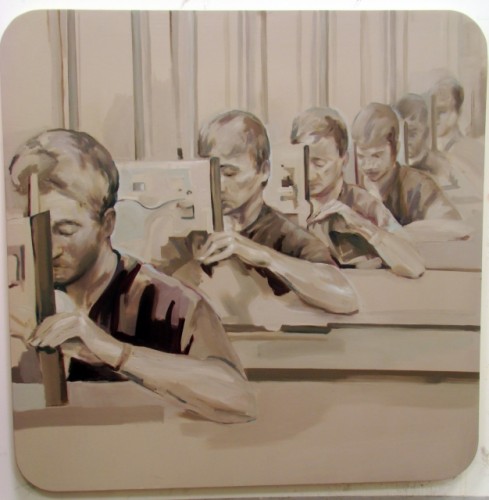

Currently I am finishing a project based on factory workers’ survey I developed, and in

return I am making works based on their requirements. I am really excited to be

almost done with it, but I will have to spare the details until I am completely finished.

I am also preparing to travel to Amsterdam for 2 month residency program with my

partner. It is very exciting and a bit frightening to leave New York for this long, but we

have to keep moving forward wherever that might be!